As a journalist I often get asked to write 'top ten tips' or 'ten ways to' or 'ten reasons why'... never six, or eight, or nine, but ten. It's got a certain feeling of completion to it, I suppose. (If we had more fingers, it might be a bigger number...) And it's a common format. I quite often see top ten destination pieces.

What editors want, of course, is a Pareto formula 80/20 - 80 percent the regular stuff, and 20 percent offbeat. So for instance if I were to write top ten tips for selling your house, eight of those tips would be basics (touch up the paintwork, tidy away the trash, make sure your garden has 'kerb appeal'), and two might be funny (make sure you don't oversleep so the potential purchasers find you in bed!) or niche (bachelors, consider putting throws over the black leather suite) or detailed (clean out the fridge).

So if I were writing an Indian top ten article for a newspaper, it would have to feature:

- the Taj Mahal

- Goa

- Jaipur

- Delhi

- Keralan houseboats

- Varanasi

- Udaipur

- Mumbai

and then I'd be allowed to mention a couple of places I really liked. For a backpacker publication the first eight might include Hampi and Rishikesh and exclude Mumbai, and a culture-led list might include a couple more World Heritage sites (Ajanta, Ellora perhaps) and exclude Udaipur or Delhi, but I don't think the lists would be very different.

Well this list

is going to be different. It's purely and simply the places I have loved the most.

- Hampi

- Mandu

- Orchha

- Bundi

- Gujarat in general.- Champaner, Palitana, Girnar

- Chanderi

- The Brahmaputra

- Trichy

- Parasnath

- The Indus Valley in Ladakh

Hampi, the former capital of Vijayanagar, is a village in a city - quite literally since part of the village has been built inside the ruins of Vijayanagar's bazaar.

It's pretty well known and pretty touristed, with a lot of guesthouses and tourist-orientated shops. But it's still small town India - tiny schoolgirls with their hair in plaits and gingham shirts tucked into grey pleated skirts walk up the road with serious faces every morning, the temple elephant goes for its bath, pilgrims sleep in the temple courtyard. I was invited to a wedding at one temple up in the hills; I talked philosophy and religion with the priest at one Shiva shrine, where cool air blew through cracks in the mountain into the cave; I chatted to a woman who'd come back to find the place she'd stayed twenty years before, and had found it. And I walked; from temple to temple, palace to palace, in the fine landscape of tumbled rocks and conical hills on both banks of the roaring Tungubhadra, in a world whose colours were so delicate and luminous it seemed to have been painted in watercolour.

Mandu, like Hampi, is a once-capital become a village; but it's not a big tourist stop; Indian tourists come to see the palaces and temples, but it's only the pilgrims who stay. I met some at the Rama temple, more at the tiny Neelkanth temple (one a raja's summerhouse) that hangs on the edge of a precipice overlooking the plains of Madhya Pradesh. I went to the evening service with some of them, who were half way through the circumambulation of the river Narmada - up one bank and down the other - carrying nothing but their puja materials in a bag; a mirror, a sacred image, incense, an oil lamp. I left early; as I sat on the veranda of my guest room at the temple, departing pilgrims waved and wished me good evening, a ceremonious kindness.

Mandu is relatively flat. But on every side of the plateau, massive cliffs fall away, and narrow gorges claw their way into the massif. Below, bright green fields chequer and stripe the plain. There are monuments of great ambition - the mosque, the tower of victory, the royal palace with its subterranean chambers where funnelled breezes and channelled water cool the air - and there are small domed tombs and miniature mosques scattered in the fields, past villages where children yell and the grated ice man comes once a day on his tricycle.

Back at the temple after my day's cycling, I talked to a young Hindu pilgrim monk. I'd thought at first he was a temple pujari, but no, he was only staying for a week or two; he dreamed of teaching meditation coupled with the Thai boxing he used to practise when he was in the world.

"Once I was in the jungle," he told me. "I went with a friend, but my friend said this is too hard, I'm going, you can die here if you want to. And I stayed in the jungle. One day I saw a leopard, very close, just like you are now, and I said: Hari Ram! if I die, I die. And the leopard looked at me and walked away. If your faith is strong, you can do anything."

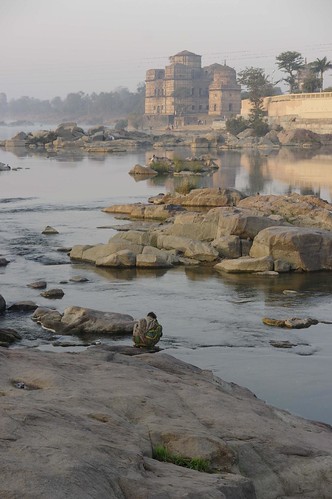

Orchha is a place where I did the wrong thing, and it worked. I let a rickshaw driver take me to a guesthouse. Temple View Guesthouse is now 'family' as far as I'm concerned. I settled in. One American tourist told me she'd 'done' Orchha; it took her three days to feel bored and constricted. After a month, I loved the place. It's another former capital, like Mandu and Hampi, with palaces, royal cenotaphs, and fine temples; but it's also a buzzing small town, when the Ramraja Temple has a festival, and people come from all over Bundelkhand; or during the marriage season, when the streets are alive with processions and sound systems, stallions wait patiently for the bridegrooms down by the river, and newlyweds with their friends visit the little garden shrine behind the Phool Mahal.

Do Orchha as a day trip and you'll be the target of hustle. Stay there a week and people get to know you; the little deaf guy and his friend from the Chaterbuj temple, Ram Babu the fruit man and 'magic fingers' (karom champion and magician both), even the children of the village and the pujari of the Hanuman temple. Orchha is my home in India. What more can I say?

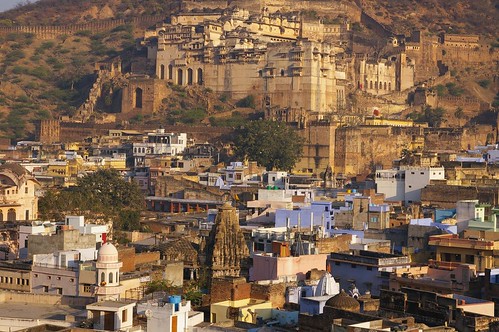

Bundi is another small town. Yes, small town India is so much nicer than city India. I accept the attractions of Mumbai, for instance (including some amazing shops for vintage Indian fountain pens, as well as colonial architecture and the tremendous cave temples at Elephanta), but the smaller towns are where my heart is. Bundi, in Rajasthan, has everything you want: palaces piled high on the sides of a hill, all pavilions and pinnacles, with the most lovely mural paintings I've seen, in which Krishna dances with the cowgirls, and Persian fairies oversee a huge military operation on the walls below; a massive fort above the town, where troops of wild monkeys roam; a bustling market, fine stepwells, and a calm lake that gleams red in the sunset. (I wish I'd stayed longer there and not gone on to Udaipur, a parody made for tourists.)

I'm going to be broad-brush with my next member of the top ten and nominate an entire state,

Gujarat. Foreign tourists just don't go there. Travel is sometimes hard - there are reliable buses, but they're hard to find out about, no one has a timetable; there are dharamshalas and small hotels, but sometimes every hotel in town seems to be full, or you end up in a workers' hotel with shared showers and toilets a long way down a gloomy corridor. But look where you end up!

The lovely town of Mandvi, where you may still see wooden dhows being built, though that industry is dying out, and where the sandy beach runs 8 kilometres out of town towards the distant domes of a royal palace; Champaner, a Hindu holy mountain sheltering a former Muslim capital where mosques and even monumental pigeon-houses dot the countryside; Palitana, a temple city where only the gods stay overnight; the high peak of Mount Girnar, where steps lead up to Jain and Hindu temples, through the morning mists to the raw sunlight; Dwarka, where Krishna devotees kidnapped me to dance in the streets with them, and fed me till I nearly burst. Even Ahmedabad has its delights: the marvellous Calico Museum with its fine textiles and bronzes, by far the best museum I've visited in India; fine mosques where jali screens give dappled light, ancient

pols with old wooden houses and fine gateways, and some of the best drinks and juice places in India (because, of course, Gujarat is a dry state).

Not far from Orchha is

Chanderi. Yet another small town, and one that didn't even make it into the edition of the Rough Guide I was using. Good. That keeps the tourists away. So does the fact that there's no guesthouse there; only a 600 rupee a night hotel. And only two restaurants, both hole-in-the-wall cafes where all the other customers were locals.

Perhaps my love of Chanderi stemmed initially from the fact that I had the luck to met Kalley Bhai, a local guide who showed me round the town after dinner and a cup of tea, for free. We wandered through the Bazar - one of the most famed bazars of the sixteenth century, though now it's a small town market frequented by cows, sleepy-eyed cats and local children - and he showed me tiny but exquisite havelis, friends who made confectionery (little hard sugar dragees, or squishy cakes), stalls selling Chanderi weaving. The weaving here is lovely, a cotton-silk mix; you hear looms click and thud in some of the old palaces. There are mosques and minarets, fine arches, extensive lakes; there's a giant Jain tirthankar carved into a cliff-face, a fort marooned above the city, tiny hills inviting you to climb them all around the town. There's one of the finest works of architecture I've seen in India, four storeys of what was a seven storey palace, where, if you dare (and I dared, though my heart was bursting through my ribs with fear), you can stand on a narrow remnant of vault and look down into the central light well.

I was invited to take tea with a young girl's family after I admired the carved door of her haveli. I spent time chatting with the confectioners. I climbed up to the fort, and wandered round the lakes, and my rickshaw driver let me sit in his rickshaw for half an hour and brought me tea while we waited for the bus, and charged nothing extra for the service. That's the kind of place Chanderi is.

Assam, like Gujarat, doesn't get as many tourists as other states, and I didn't have enough time to see it properly, just a few days in Guwahati and around. (For some reason, as soon as I arrived in Guwahati everyone assumed I wanted to get out of it - "Shillong, Shillong," the bus-touts chorused. But I stayed.) The

Brahmaputra, for me, is one of India's genuine highlights - nearly two kilometres wide, with temple-crowned islands scattered across its braided channel, and tiny square-sailed boats carving its grey waters. Assamese temples are unlike those anywhere else in India, with open, wooden mandapas in front of gloomy shrines with huge stone pillars

that crowd in, rising high above; inside, the darkness swims, heavy

with incense.In one, the nine planets have their own small hearth-altars, with lamps and fires shining in the dark. In others, steps in the sanctuary lead down to a slash in the rock where a spring or stream flows, symbol of the dark goddess. Majuli, upstream, is a marshy, massive island full of small wooden shrines; or further downstream there's Hajo, a delightful town that surprised us with its hospitality and with its looming temple on the hill above a tank where huge fish come to be fed, and turtles lurk in the green water.

Tamil Nadu is the temple state, and I love

Trichy for its combination of fine temples and a buzzing modern city. The Rock Fort amazingly combines a hilltop temple with views across the wide Carvery river and the plain with cave temples dug into the rock; in one mandapa I found a man sitting on a mat, chopping vegetables - the temple provides a charitable lunch for the poor. Across the river lies the Srirangam Temple, which holds an entire town within its multiple, concentric walls; and the Jambukeshwar temple, a little further out, has a huge tank full of water hyacinth, soaring gopuras, dim corridors, and gardens full of tall trees. But from the Rock Fort it's just a few minutes' walk to the shopping malls full of consumer electronics, or the grocery market where red-skinned onions roll across the pavement and buyers thrust their hands into sacks of rice to assess the quality.

Bihar is off most tourist maps, but if you are interested in either Buddhism or the Jain religion, you'll end up there - at Pawapuri where the last great Jain teacher, Mahavir, died, or at Bodh Gaya where Buddha received enlightenment, or at

Parasnath, the great Jain pilgrimage mountain.A day on Parasnath involves 18km of walking, and about 1 km of ascent, and there are also visits to temples and shrines off the main route to be factored in. It's hard. It's very hard.

I was about two-thirds of the way up when exhaustion hit me. My legs were solid pain; I could feel tears starting in the corners of my eyes. The rucksack straps had numbed my shoulders. I nearly gave up. A dholi passed me, a sedate old gentleman on his litter with four bearers propelling him upwards; he smiled, I scowled.

"It's hard," a girl said.

"Yes," I said; and at the same time I realised she'd spoken in an American accent.

It turned out the whole family were climbing Parasnath together. The senior generation in their dholis, the younger on foot, and fasting, and her brother - languid and elegant in a long white kurta - barefoot, too; "because Dad is always going on about how things were much harder in the old days, and I'm not going to let him do it this time." They'd started before dawn; they were tired; they had one more temple to visit before they got to the top. They gave me new strength.

It's worth the climb. The temple at the top is nothing much, architecturally; but the views over the foothills and the huge low plain, and the forested slopes scattered with bright white temples, and the cool, fresh air, and the sound of chanting and bells, and the knowledge that you've done your duty, you've walked those long, dusty, painful kilometers (and it's all a long downhill yomp back to the dharamshala from here) - it's hard to describe how good that is. How it heals the soul. That's Parasnath.

Varanasi has to be on my list, I suppose. I rather thought none of the regular top ten would make it, but Varanasi is something special. There's hustle, from "Madam boat madam boat" to "I am Brahmin, madam, I am living here and reading philosophy," to the men who want to sell you silk which turns out to be polyester, and at higher prices than the genuine article from the big silk Mehrotta factory shop, to the guys who frequent the burning ghats and want you to stump up the price of a bit of wood (and I know my wood, having been responsible for buying a good bit of prime rosewood, cedar, and spruce, but most UK timber yards don't sell it with gold leaf on both sides, which must surely be the case given the amount these chaps want for stuff that's only going to feed the fires).

But... the light in Varanasi is different. It's as if the Ganges infuses liquidity into it; the light is soft, luminous, delicate, from morning mists to afternoon sunlight. The narrow galis of the old city hide palaces, ancient temples, tiny dark squares where huge trees sway above; there are market stalls selling wooden toys and gilded bronze bowls, mouth-freshening sugar-coated fennel seeds and bottles of palm oil, and Varanasi glass beads that tinkle and glitter. Above all, there's the Ganges, huge and sluggish, or rapid and hungry in monsoon, and the immense flights of steps which rise up from the tiered ghats towards the city, topped by palaces and temples, spires and minarets. Varanasi surprised me with light and shade. It's the sacred centre of India; how could I leave it out?

This list is a little biased to the north. (Though not the far north; not Ladakh, which I love, but which frustrates me with its bias to neatly packaged treks, and where perhaps I need to go with a motorbike to appreciate it properly; not Chamba, though it's a lovely place, with its ancient small temples in their compound, and its dusty Chowgan in the centre of town, and the great hills all around, and the wonderful mountain pasture of Khajjiar, and the tiny temple town at Bharmour, a twisting, frightening couple of hours on the bus; not Rewalsar either, with its lake in the mountains and its easygoing Buddhist monks and Tibetan chefs and the attractions of cheap, and highly alcoholic, cider.) I didn't want it to be; I love the south. I love Madurai, with its temple that you can stay in all day and not be bored, a huge, living temple pullulating with rites and chants and crowds. But it's a horrible city, full of mud and bad hotels. I love Kanchi with its many temples and its courteous people, and Bijapur with the huge hulk of the Gulbumgaz and the delicate tomb of Ibrahim Rauza, better than the Taj Mahal and far less crowded. I love Gokarna on the sea with its beaches, where the cow tried to get into the teashop, and the temple corridors are dim with smoke and incense, and pilgrims bathe in the ocean at dawn and come out with their loincloths wet and their mobiles dead if they forgot to put them safely on the sand. I have a very soft spot for Lonavala, which combines the attractions of early Buddhist cave temples with the temptation of locally made

chikki, nut brittles and nougats for which the town is famous. It's a tragedy that the top ten format forces me to leave them out... but none of them

quite made it.